Children can be tricky to refract. Depending on how cooperative the child is willing or able to be, practitioners may find themselves struggling to gain any meaningful subjective or objective refraction results. Refraction challenges in children are explored in this case that SK shared with the Myopia Profile community. This is not a case of a myope, but with more myopia management comes general paediatric management and hence cases such as these. What would you prescribe for a child with such findings?

It is useful to have a mental checklist of clinical considerations in prescribing for children.

1. Is there a risk of amblyopia?

Based on the autorefractor results, the child has significant astigmatism in both eyes. According to Donahue et al, the refractive errors that place for children aged > 48 months at risk of amblyopia are >1.5 D astigmatism, >1.5 D anisometropia, and >3.5 D hyperopia.1 In this particular instance, there is a chance that this child may become amblyopic in both eyes, especially in the right, if this refractive error is not corrected.

2. Which refraction technique is best?

The first important factor for discussion is the technique of refraction. The child in this case is aged 5, and described as being ‘unresponsive to subjective refraction’. The recommended refraction technique for a child of this age is retinoscopy, as described by both Optometry Australia and the American Optometric Association in their respective paediatric eye care guidelines. Optometry Australia recommend retinoscopy as the primary refraction technique for children aged from birth to 7 years. The American Optometric Association recommends retinoscopy is the preferable technique, with autorefraction best used as a starting point for other refraction techniques. If autorefraction is the only technique available, research indicates that its accuracy improves with cycloplegia,2 as was undertaken in this case. To read more about when to use cycloplegia in paediatric refractions, read our blog How to achieve accurate refractions for children. Let’s explore the discussion that occurred around refraction techniques.

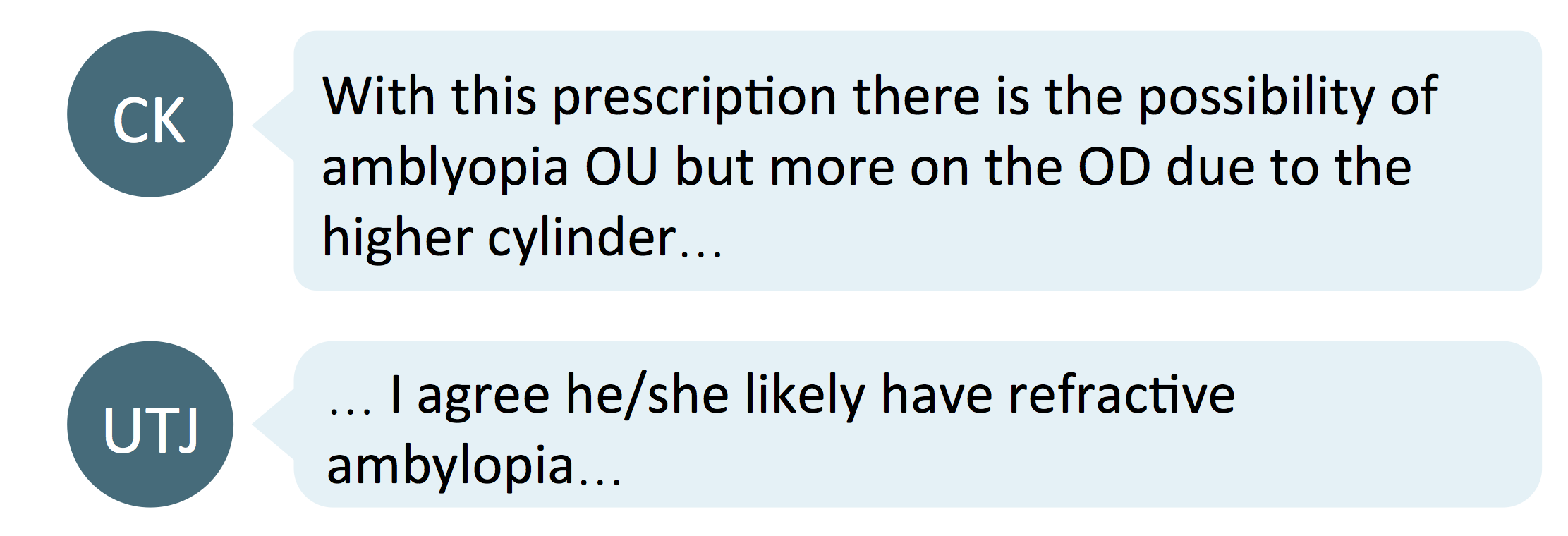

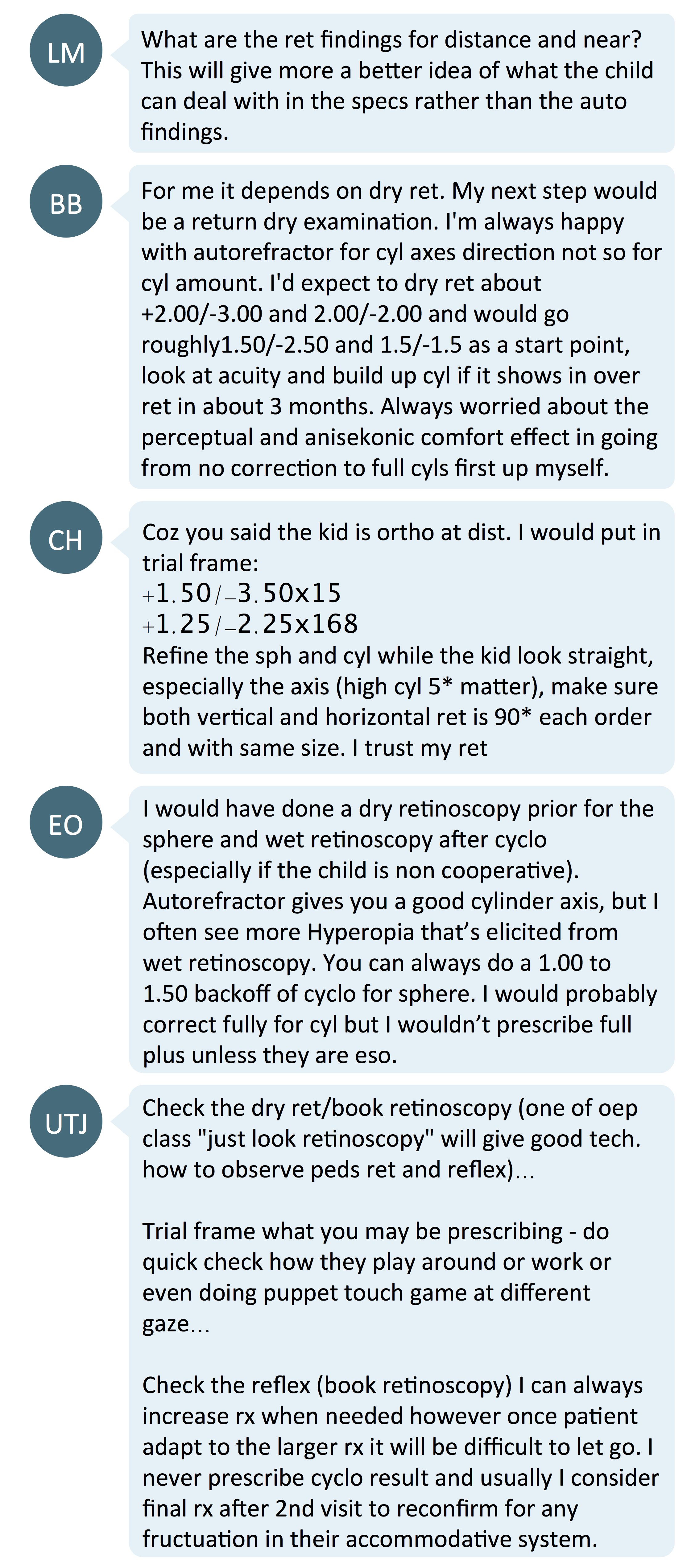

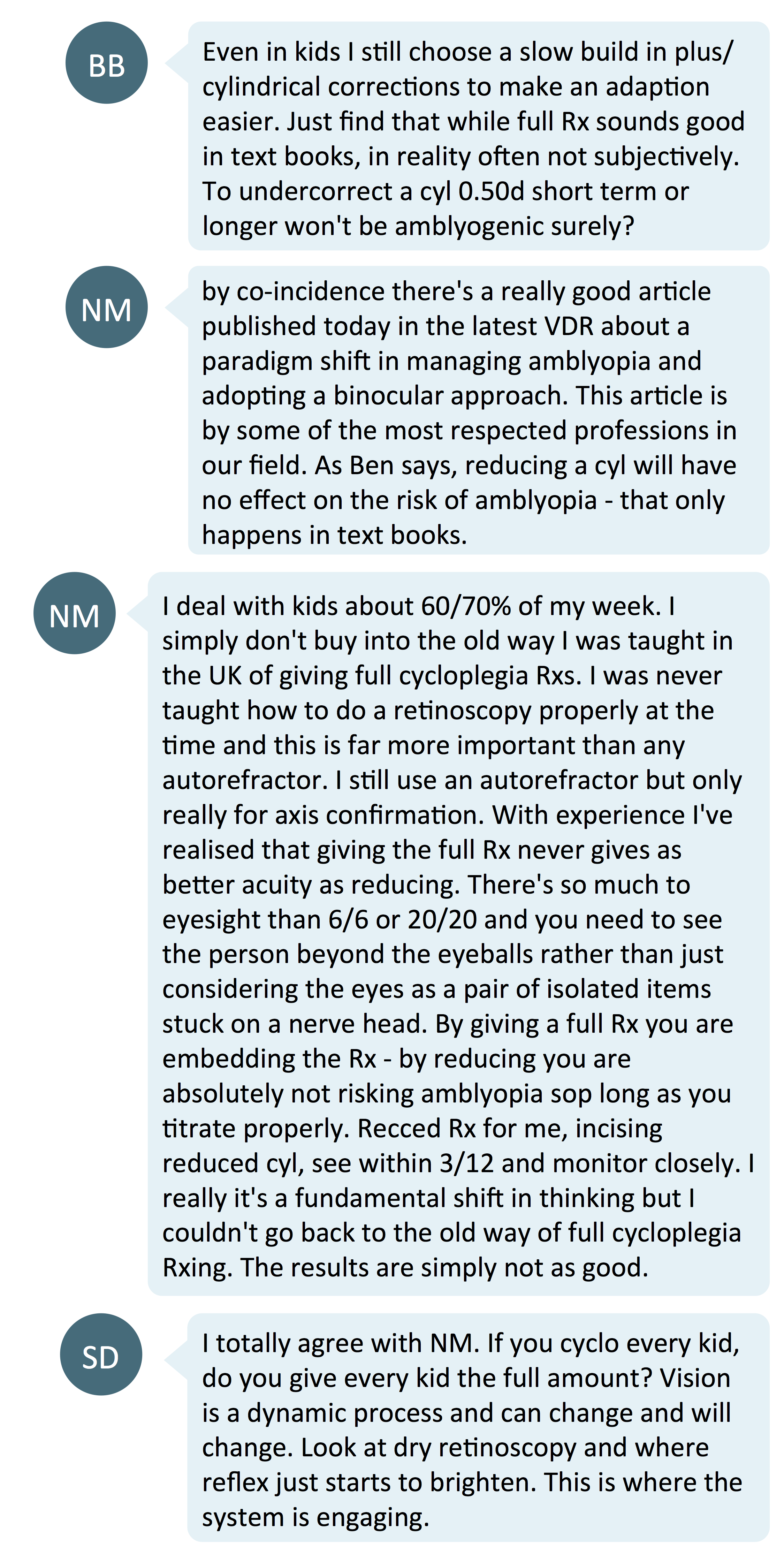

Autorefractor Vs. Retinoscopy

Many commenters concurred with guidelines from professional organizations, as indicated above, that dry or cycloplegic retinoscopy results would influence the decision on prescription. The comments suggest that autorefractors are handy for confirming the cylinder axis, but results for the degree of sphere or cylinder need to be refined by retinoscopy as the autorefractor is less accurate.

How accurate are autorefractors?

- Choong and Wesemann showed that the results of autorefractors are accurate under cycloplegic condition whilst over-minussing under non-cycloplegic conditions.3,4 (autorefractors used: RETINOMAX K PLUS, CANON RF10, GRAND SEIKO WR5100K, RETINOMAX)

- Hashemi showed that autorefractors tended to over-plus hyperopes and over-minus myopes when compared with cyloplegic retinoscopy. However, both methods corroborated and the difference was declared as clinically insignificant.5

- Under cycloplegic conditions, the result of autorefraction and retinoscopy were similar for Indian children over 6 years of age in a study done by Guha et al. But, they included a caveat that the autorefraction result of children with mixed astigmatism, or under 6 years old, should be confirmed with retinoscopy.6 (autorefractor used: TOPCON KR-8900)

- Prakabaran et al compared the results between a hand-held autorefractor, table-mounted autorefractor and retinoscopy. The table-mounted autorefractor gave similar results to retinoscopy whereas hand-held auto refractors gave slightly different results to table-mounted auto refractor and retinoscopy.7 (table-mounted autorefractor: CANON FK-1, hand-held autorefractor: RETINOMAX)

These studies indicate that autorefraction is almost accurate as retinoscopy when cycloplegia is used, but is unlikely to substitute for retinoscopy in children under 6 years of age, or those with high refractive error.

The American Optometric Association's Clinical Practice Guideline on Pediatric Eye and Vision Examination (pg 23) states that "autorefraction may be used as a starting point for subjective refraction, but not as a substitute for it; however, retinoscopy, when performed by an experienced clinician, is more accurate than automated refraction for determining a starting point for non-cycloplegic refraction." This was advice for school aged children, from age 6 to 18 inclusive. In clinical practice, it is ideal to confirm the refractive error with retinoscopy. Non-cycloplegic retinoscopy can also give you binocular vision insights as well - such as near lag of accommodation with near retinoscopy.

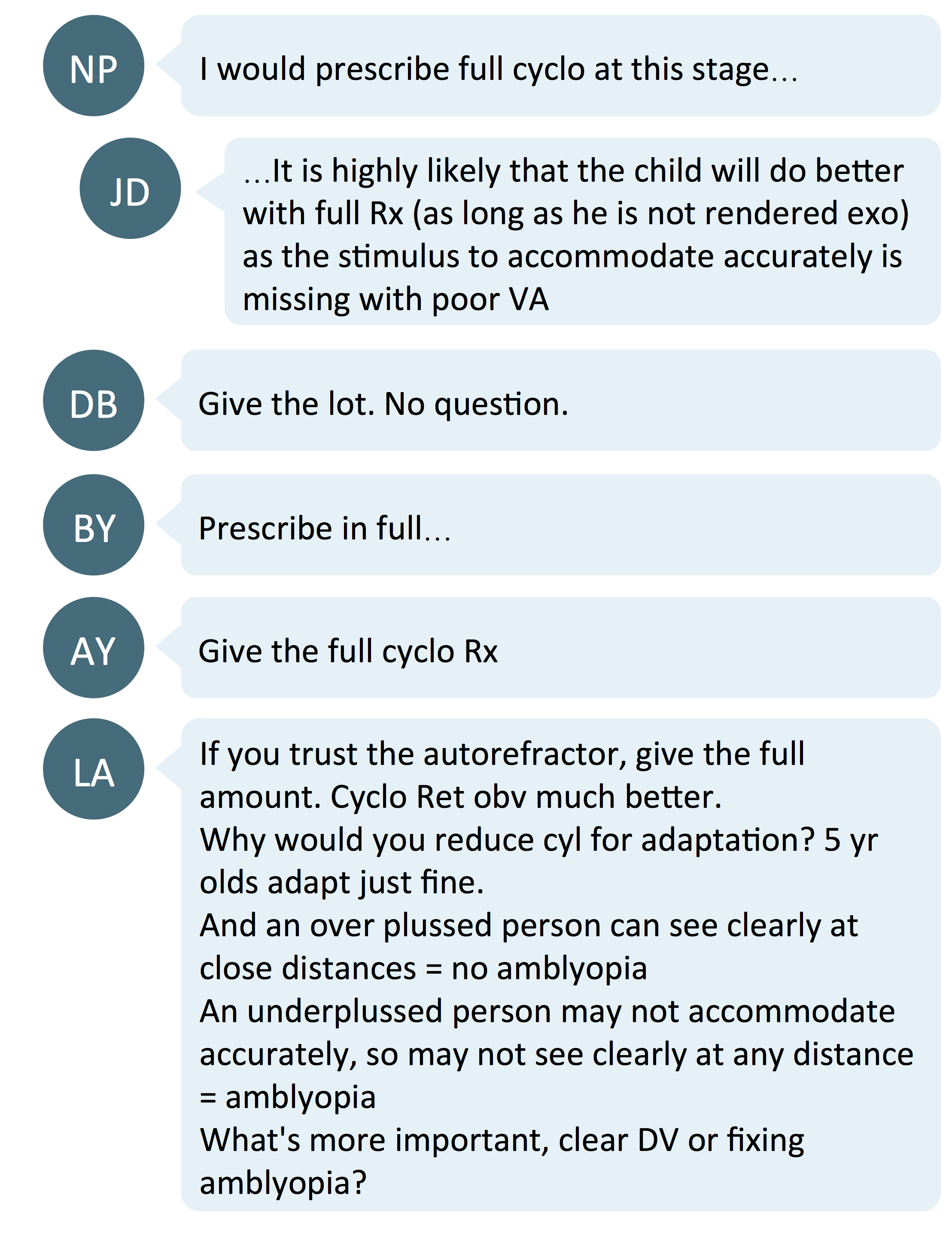

3. Full versus partial correction - which to prescribe?

Team Full Correction

There was a group of practitioners supporting full correction for a few reasons:

- That it would be better for the child’s accommodation and yield better acuity to avoid amblyopia

- That children can adapt to high cylinder corrections quite easily so there is no need to start with a partial script.

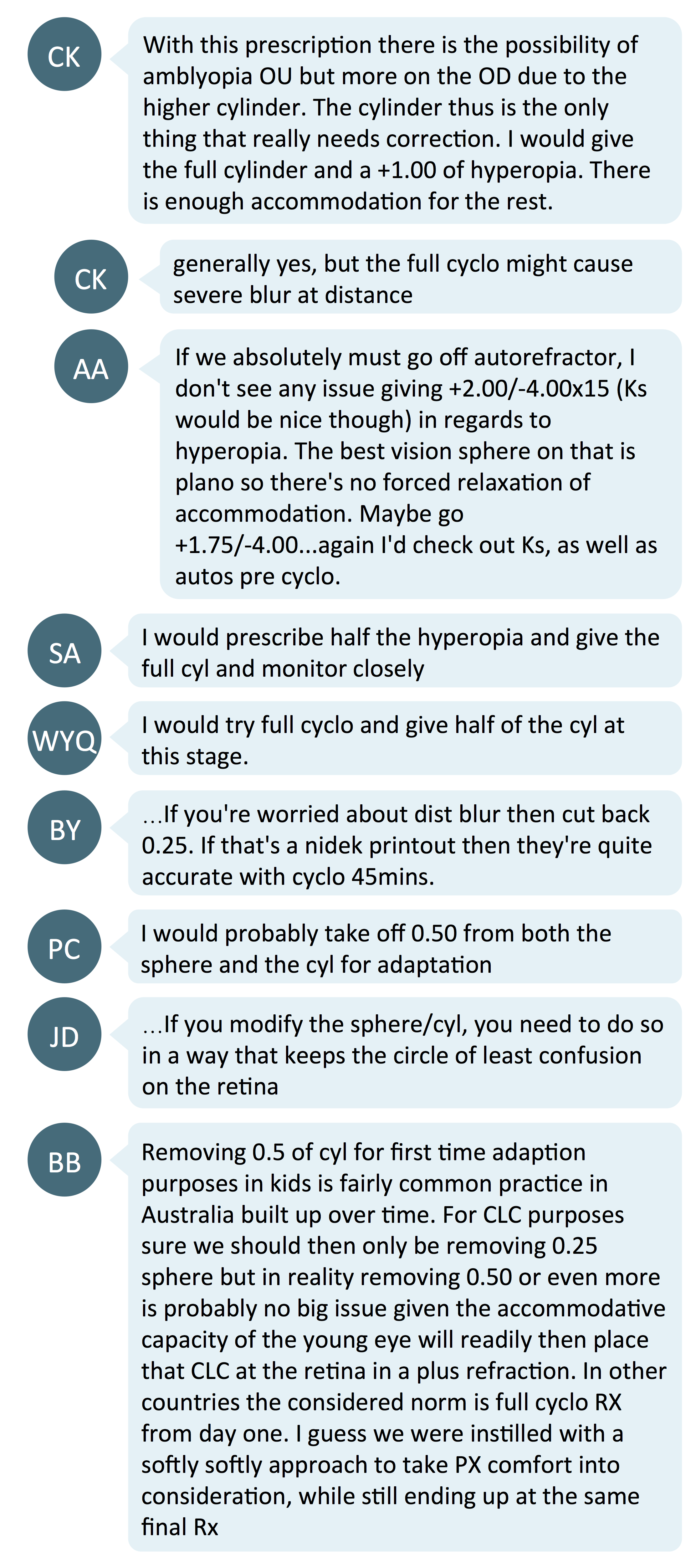

Team Partial Correction

On the other hand, the majority of the commenters would prefer to prescribe a slightly reduced correction for both the hyperopia and astigmatism. A 0.50D reduction in sphere or cylinder is mentioned most frequently in the comments. There was mention of reducing the prescription such that one maintains the circle of least confusion (i.e. reducing 0.25DS for every 0.50DC change).

Commenters’ concern with partial spherical correction is that it may adversely affect the child’s accommodation whereas the concern for partial correction in cylinder is it might allow amblyopia to become more embedded. The main reasons for partial correction are for easier adaptation and that a full cycloplegic prescription may blur distance vision. Susan Cotter’s paper suggests that an optometrist’s decision on how much plus to prescribe in childhood hyperopia often considers the child’s visual function with the prescription, and these include allowing for robust function of accommodation, vergence, stereopsis and near vision.8

What the literature says:

- Prescribe full cycloplegic correction for hyperopes with esotropia. If esotropia is absent, slight under-correction can be prescribed.9-12 The purpose of under-correction is to allow some accommodation.9 The child does not need full correction for good vision10 and under-correcting can act as stimulus for emmetropization.11,12

- No under-correction is needed for astigmatic correction.9,10 Children are able to adapt to high cylinder power correction.9 For first correction, mild under-correction can be given for adaptation.10

- Harvey et al showed that best corrected acuity improved from 20/51 (6/15) to 20/40 (6/12) after 4 months of spectacle correction in 3-5 year old kids with astigmatism. Both myopic/mixed and hyperopic astigmatism groups had similar improvement. Astigmatic correction of at least 2DC was given full correction in 3 to <4 year olds and at least 1.50DC for children 4 years and older.13

- Roch-Levecq et al showed gradual improvement in visual motor integration related scores in preschooler after 6 months of spectacle correction.14 Ametropia correction was determined by cycloplegic retinoscopy as bilateral hyperopia ≥ 4 D in 3 to 5-year olds, astigmatism ≤ -2 D in 3-year olds and ≤ -1.50 D in 4- and 5-year olds, or a combination of both, and emmetropia as ≤2 D and ≥ -1 D in both eyes.

In summary, giving mild under-correction in hyperopia and astigmatism is an acceptable game plan. However, if the patient has esotropia, it is important to prescribe the full hyperopic correction from cycloplegic results; or if adaptation is a significant concern, start with an initial reduced prescription, building up to the full prescription. To read more about thresholds for prescribing in young children (up to 6 years of age), read our blog entitled How to manage the very young myope.

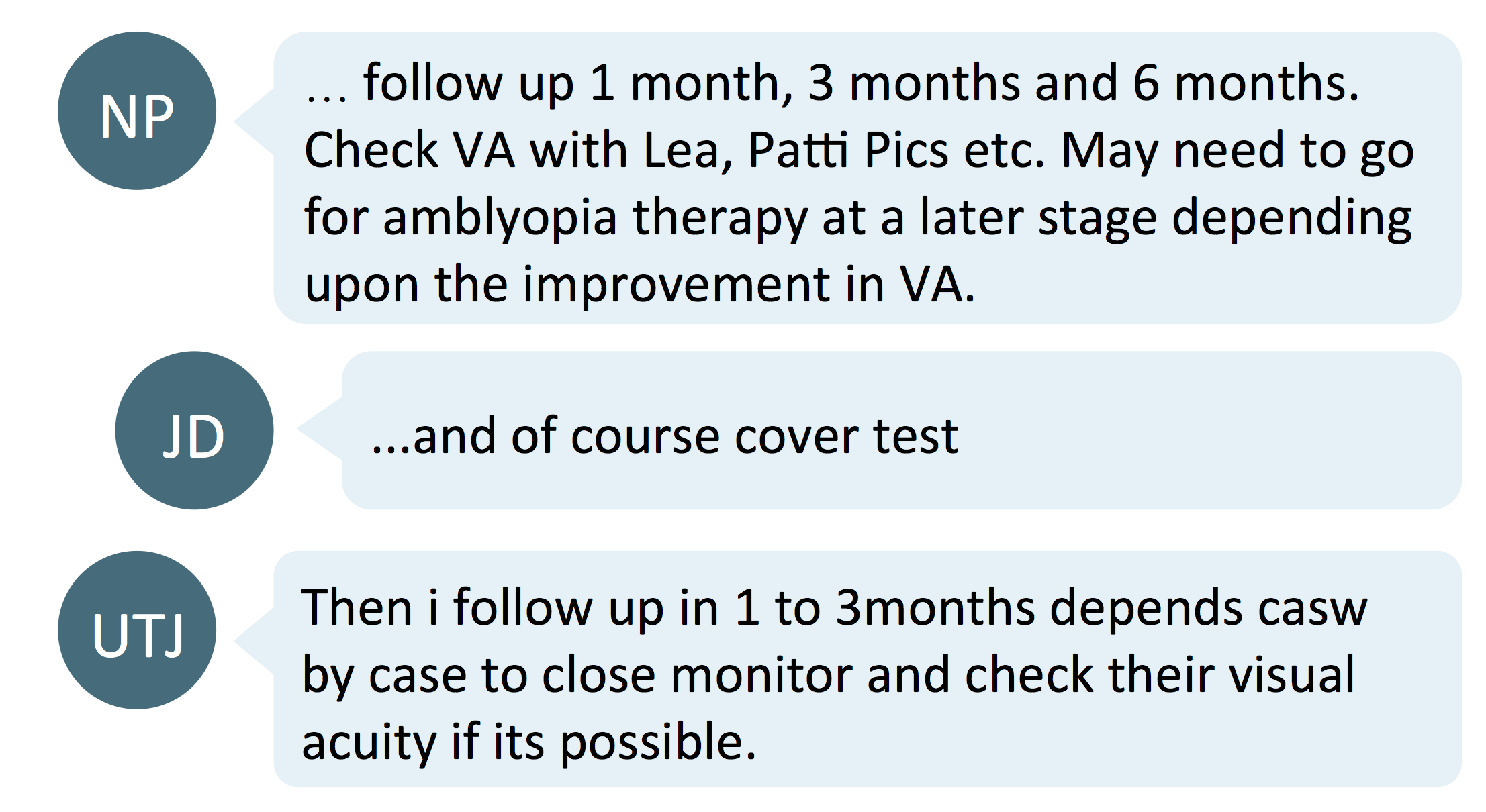

4. When to follow up

As noted in the original post, the child was reported to only achieve a binocular best corrected acuity of 0.6 Decimal, which is a little worse than 20/32 or 6/9.5. Hence, close follow up is required to monitor improvement and manage any emergent amblyopia. During the follow up, we would need to assess:

- Visual acuity - to monitor amblyopia

- Binocular vision status - to rule out any strabismus influencing gains in acuity, especially any esotropia/ high esophoria in this case if partially corrected

- Keratometry/topography (where possible, due to age) - to monitor corneal as compared to refractive astigmatism.

Take home messages:

- In measuring paediatric refractions, we can use objective measures like retinoscopy and autorefraction results for patients where subjective measure are not possible. The research and consensus indicates, though, that retinoscopy is the preferable technique.

- Most colleagues agree to slightly under-correcting hyperopes and even astigmatic corrections by around 0.50D. Typically we would not under-correct myopes, although guidelines for prescribing in myopic children up to 6 years of age indicate that this may be suitable up until age 4 for myopes, but full correction after age 4 is preferable.

About Kimberley

Kimberley Ngu is a clinical optometrist from Perth, Australia, with experience in patient education programs, having practiced in both Australia and Singapore.

About Connie

Connie Gan is a clinical optometrist from Kedah, Malaysia, who provides comprehensive vision care for children and runs the myopia management service in her clinical practice.

This content is brought to you thanks to an unrestricted educational grant from

![]()

Reference:

- Donahue SP, Arthur B, Neely DE, Arnold RW, Silbert D, Ruben JB, AAPOS Vision Screening Committee. Guidelines for automated preschool vision screening: a 10-year, evidence-based update. Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2013 Feb 1;17(1):4-8. (link)

- Sankaridurg, P. et al. Comparison of noncycloplegic and cycloplegic autorefraction in categorizing refractive error data in children. Acta Ophthalmologica 95, e633-e640, doi:10.1111/aos.13569 (2017). (link)

- Choong YF, Chen AH, Goh PP. A comparison of autorefraction and subjective refraction with and without cycloplegia in primary school children. American journal of ophthalmology. 2006 Jul 1;142(1):68-74. (link)

- Wesemann W, Dick B. Accuracy and accommodation capability of a handheld autorefractor. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery. 2000 Jan 1;26(1):62-70. (link)

- Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Asharlous A, Yekta A, Emamian MH, Fotouhi A. Overestimation of hyperopia with autorefraction compared with retinoscopy under cycloplegia in school-age children. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2018 Dec 1;102(12):1717-22. (link)

- Guha S, Shah S, Shah K, Hurakadli P, Majee D, Gandhi S. A comparison of cycloplegic autorefraction and retinoscopy in Indian children. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2017 Jan;100(1):73-8. (link)

- Prabakaran S, Dirani M, Chia A, Gazzard G, Fan Q, Leo SW, Ling Y, Au Eong KG, Wong TY, Saw SM. Cycloplegic refraction in preschool children: comparisons between the hand‐held autorefractor, table‐mounted autorefractor and retinoscopy. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2009 Jul;29(4):422-6. (link)

- Cotter SA. Management of childhood hyperopia: a pediatric optometrist's perspective. Optometry and Vision Science. 2007 Feb 1;84(2):103-9. (link)

- Sainani A. Special considerations for prescription of glasses in children. Journal of Clinical Ophthalmology and Research. 2013 Sep 1;1(3):169. (link)

- Leat SJ. To prescribe or not to prescribe? Guidelines for spectacle prescribing in infants and children. Clinical and experimental Optometry. 2011 Nov;94(6):514-27. (link)

- Sharma P, Gaur N. How do we tackle a child's spectacle?. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2018 May;66(5):651. (link)

- Wutthiphan S. Guidelines for prescribing optical correction in children. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005 Nov;88(Suppl 9):S163-9. (link)

- Harvey EM, Dobson V, Miller JM, Sherrill DL. Treatment of astigmatism-related amblyopia in 3-to 5-year-old children. Vision research. 2004 Jun 1;44(14):1623-34. (link)

- Roch-Levecq AC, Brody BL, Thomas RG, Brown SI. Ametropia, preschoolers’ cognitive abilities and effects of spectacle correction at 6-month follow-up. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2008 May 14;49(13):1427. (link)